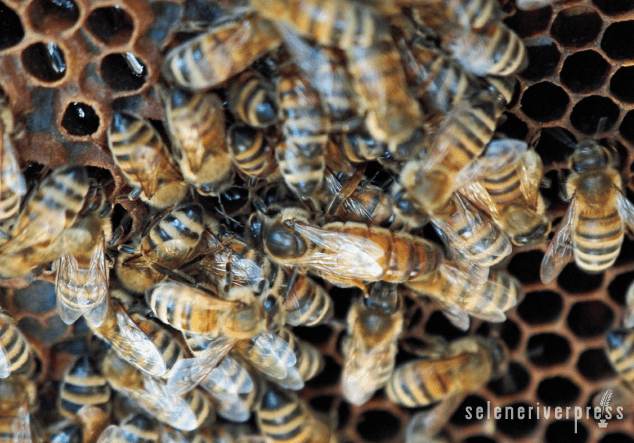

There are three castes in the honeybee world: queen, drone, and worker. There is typically only one queen per colony. The rest of the female honeybees are called workers because they do all the work. The queen lays eggs, end of list. The drone provides sperm, end of list. But the workers’ list never seems to end. In fact, it’s so long that I can’t fit the whole description in a single article. This time, I need two.

In this two-part series, I won’t cover detailed anatomy and physiology—unique and interesting as that is. The focus here will be on the chores that workers perform in their brief lifetime, in that a worker never lives to see her first anniversary (C.P. Dadant, First Lessons in Beekeeping, revised 1951, p. 23).

Keep in mind, a worker starts exactly like a queen, but she’s fed a different diet and her reproductive system never fully develops. Therefore she cannot mate and lay fertile eggs. To further describe workers, we must also distinguish between cold season workers and warm season workers, as well as young workers and older workers. Finally, we must note the many specialized, sometimes very temporary, skills they perform.

There’s no rugged individual in a honeybee colony. The colony is everything. Individual workers resemble human body cells more than they do human individuals. From the moment they emerge, everything workers do contributes to colony success. They never experience a selfish moment.

Let’s go back and start at the beginning. It’s a very good place to start. A worker begins as a fertilized egg (Starting Right with Bees, A.I. Root Publishing, 1976, p. 11). This is different from her brothers, who all start as unfertilized eggs. An egg is an egg for three days, then it hatches into a larva, a hungry little worm that immediately begins consuming royal jelly. A worker performs all the nursing duties, including feeding 1,300 times each day (Beekeeping for Dummies, Wiley Publishing, 2002, p. 33) and maintaining the correct temperature. This continues for days four, five, and six. Then the diet changes to a mixture of bee bread and honey for days seven, eight, and nine. On the ninth day, the growing larva is capped so it can spin a cocoon. Within the cocoon it undergoes a metamorphosis, transforming into a pupa. Maturing continues under the wax cap until day 21, when the adolescent bee chews her way through the cap to emerge.

A bee raised to perform winter duties has relatively little to do. Consequently, she may live as long as six months. She joins the cluster near the outermost layer, called the mantle. There she begins to vibrate her flying muscles, which detach from her wings for this duty. Beekeepers call this shivering, and it creates kinetic heat. While shivering, she slowly migrates inward toward the center of the cluster, where the colony maintains a temperature of 92–95ºF. Having arrived near the center, she’s completely up to temperature, and her muscles are fully operational. This is her chance to use her mobility to break free of the cluster and get some honey to eat. With a tummy full of carbohydrate, she rejoins the cluster at the mantle and begins burning calories by shivering again. She will repeat this process for the entire cold weather season. When the temperature drops below 50ºF, honeybees are generally in cluster.

When the temperature gets above 50ºF, the dutiful workers take advantage of the opportunity for a cleansing flight. They need to poop. (They will not, under normal circumstances, soil the inside of their hive. Only a colony illness would bring that on.)

Shiver and eat, shiver and eat, shiver and eat again. That’s the life of a cold weather worker, with relatively rare interruptions to fly and poop or raise some new bees, especially as spring approaches.

But warm weather duties form a much longer list. Not surprisingly, many more bees are needed, and they generally work themselves to death in about six weeks.

We’ll break the warm weather list into two dominant time segments: the time spent by younger workers inside the hive and older workers outside the hive. Though these time frames mostly assume warm weather, remember that honeybees must raise small amounts of brood in the cold months also. The inside time lasts about two weeks (Starting Right with Bees, p. 11). The outside time lasts the remainder of a worker’s short life.

A younger worker spends her days in the hive, where it’s safe and warm, performing mostly housekeeping and nursing duties. The newly emerged worker might get a day or so to get acquainted with the hive and fill her stomach with plenty of honey and bee bread, but then she immediately gets to work. Her first duty is to clean cells of debris (cocoon and other waste) in preparation for a new egg. A nurse lines each brood cell with propolis for hygiene before the new egg is laid. The nurse also soaks the egg in just the right amount of royal jelly and maintains temperature control right up to the day the larva in the brood cell gets capped. The nurse bee glands that produce the royal jelly will eventually atrophy as a new set of glands capable of producing wax become active at about day 12 (Kim Flottum, The Backyard Beekeeper, 2005, p. 35). Capping brood is a duty for older nurses.

Nurses must also feed the drones. How sad that drones can’t even feed themselves! Their diet is honey and bee bread.

Every living thing must have food, including protein and carbohydrates. For developing honeybees, the royal jelly provides both in the early days. Nurse bees eat bee bread to stimulate their glands and produce royal jelly. Older larvae are capable of eating bee bread for protein and honey for carbohydrates. The nurse bees bring the honey and bee bread to each developing larva cell.

But how does that bee bread get made? Foragers first deliver pollen to the hive. Housekeepers mix the pollen with enzymes and honey, then they pack the bee bread into cells using the top of their head. The bee bread ferments slightly as a preservative. This stored protein is ready and waiting whenever a nurse bee may need it in the future.

Likewise, foragers deliver nectar to the hive. Housekeepers wait near the entrance to accept the nectar and haul it to the cell, where it will be stored. The nectar arrives as 80 percent water and must be cured down to 18.6 percent or less to become honey. When fully cured, the honey cells must be capped with a layer of wax because honey can breathe moisture in and out. The wax capping seals the honey for long-term storage. Honey capping is a housekeeper job.

How did the wax comb cells get made for raising brood and storing food? Secreting wax and forming the comb cells is also housekeeping. Young workers with active wax glands use their toothless mandibles, which bite sideways, to form the comb. Honeybee comb is made up of cells of various sizes on both sides of a midrib—it’s all wax and perfectly built for honey, workers, drones, and even queens when necessary.

The duties and skills of honeybee workers vary widely, and they change with age. What we’ve learned thus far applies mostly to younger workers, two weeks emerged or less. The next article will discuss the remainder of the worker’s surprisingly brief life.

Be sure to check back here for Donald Studinski’s “Wonder and Awe Workers, Part 2” on March 27.

(Photo credit: Steve Kennedy)