One of the most confounding beliefs of modern medicine is that a person is either completely lacking in a vitamin or not lacking it at all. The idea that there are in-between states of vitamin deficiency and that such “subclinical” deficiencies are the cause of common illnesses is perplexingly dismissed by the medical community.

Everyone knows, for instance, that over time a total absence of vitamin C leads to the dread disease scurvy. But as Dr. W.J. McCormick pointed out in a 1962 article in the Journal of Applied Nutrition, even a partial deficiency of the vitamin is associated with a host of familiar woes, including arthritis, infection, heart disease, and cancer. But perhaps the most surprising condition McCormick mentions is the “striae of pregnancy,” or stretch marks.

“Striae are produced,” McCormick notes, “by the rapid and extensive stretching of the skin and underlying connective tissues in the presence of decreased elasticity of the same.” Given that a deficiency of vitamin C “is conducive to decrease in tensile strength of tissues generally,” he says, subclinical deficiency of vitamin C is very likely “the culpable etiological factor” behind stretch marks.

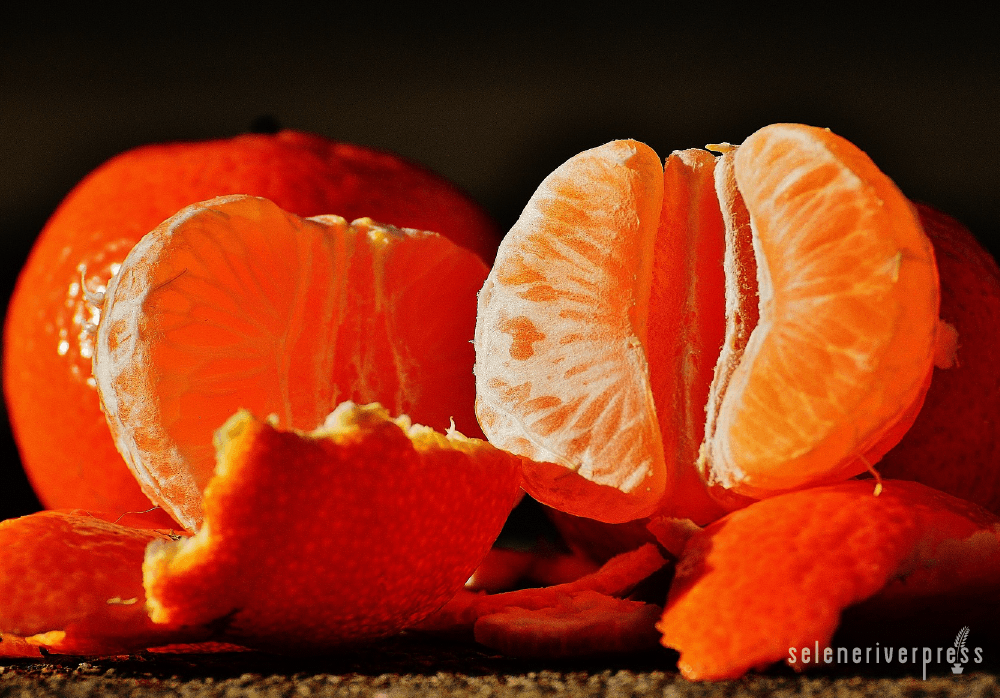

Indeed, McCormick adds, in a clinical survey of twenty-six pregnant women, the degree of stretch marks in the subjects was found to be inversely proportionate to the level of vitamin C in their body. Interestingly, only fifty percent of the women exhibited stretch marks at all, down from a rate of about ninety percent a century earlier—a decline the doctor attributes to “the increased consumption of citrus and other fruits of high vitamin C content within the last century.”

Conspicuously omitted in Dr. McCormick’s assessment is any mention of citrus juices, whose vitamin C level is severely diminished by the process of pasteurization. Perhaps he knew that when it comes to nutrition, the difference between a whole food and a processed one is often all the difference.